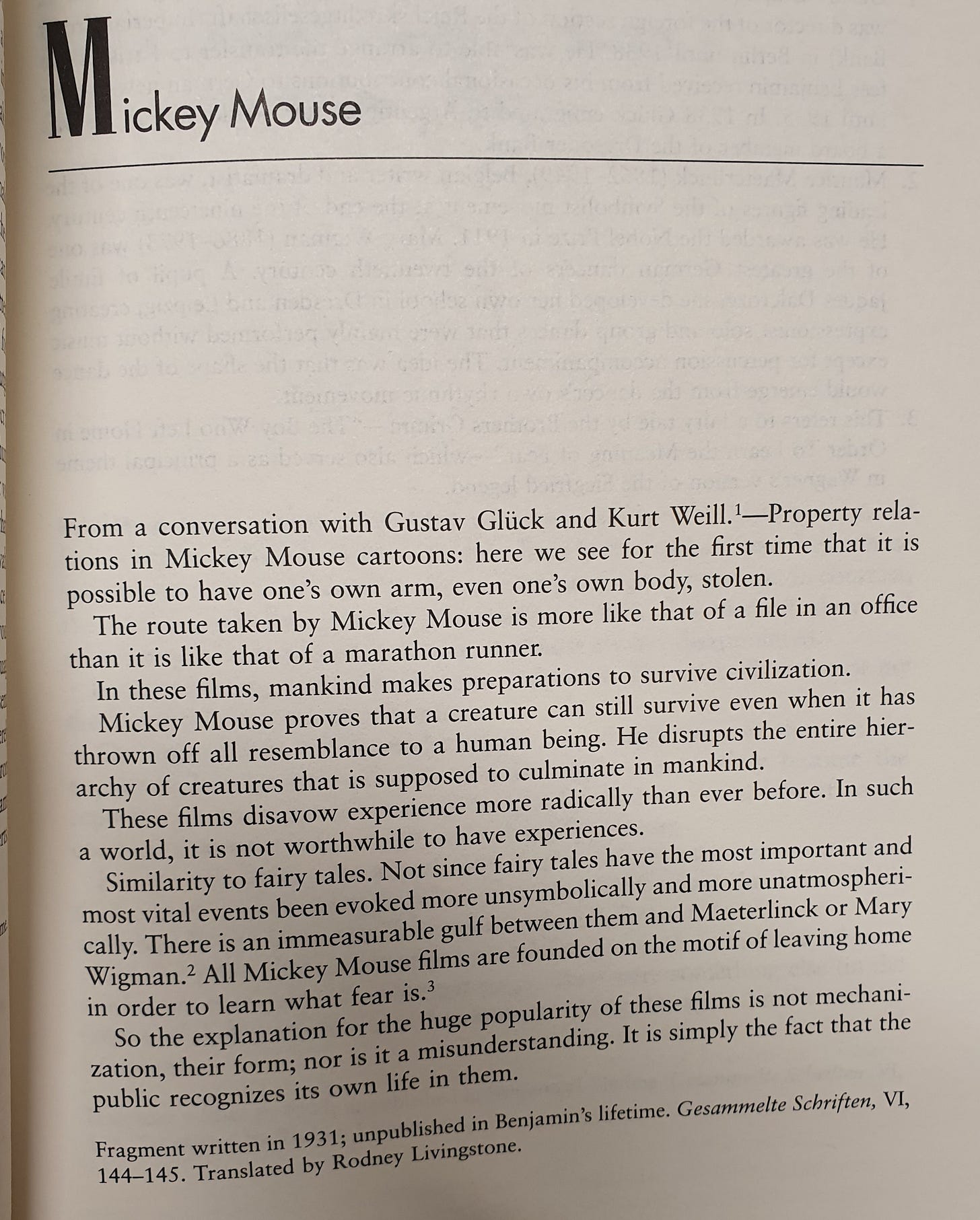

Walter Benjamin and Mickey Mouse

Flicking through my five volume collection of Walter Benjamin’s complete writings I stumbled upon a curious fragment on Mickey Mouse. Written as a short note in 1931, and unpublished during his lifetime, he captured a few fleeting thoughts after a casual conversation with friends. Benjamin was, of course, interested in emerging forms of modernity and how consumer capitalism and mass media were transforming experience and social life. Perhaps more crucially he was also interested in how stories and storytelling document the times. This might be why his attention was drawn toward this cartoon mouse and what the character’s presence might reveal.

To my knowledge he never returned to write more on Mickey Mouse. This fragment is all I’ve found. Yet it seems that in this passing moment the cartoon figure captured his imagination, sending it flying in a number of directions. He had been writing on radio and photography at around the same time too, with short pieces on both written in the same year. The sudden focus on Mickey Mouse could be seen to be quite close to those interests. Still, most of his works from that period were much more literary in subject matter - and included his famous essay on the book collector. It was a few years before his major and most famous essay on art and reproduction would be complete.

In 1931 Mickey Mouse was enjoying a similarly productive period. Building on a sustained period of outputs, the early 1930s saw significant successes. A series of films were released in 1931 alone, including Mickey Steps Out, The Birthday Party and The Moose Hunt. Perhaps it was the sheer popularity of the lead character that led Benjamin to engage in this discussion with his friends. Mickey Mouse represented the pinnacle of popular culture. Or maybe the animation was a very literal form of the reproduction Benjamin would soon go on to write about.

The notes themselves are a little more difficult to interpret. Short and sketchy they are really only glimpses of his thinking. The piece reads as a series of brief thoughts - presumably quickly jotted so as not to be lost. The incomplete nature of the thoughts and the lack of description leaves each sentence hanging. There is an obvious ambiguity; the points aren’t quite finished. The notes contain some very open ended attempts to link the cartoon to wider thoughts. In fact, it’s a little chaotic and the points are quite stretched. The little piece probably tells us as much about the sparking of Benjamin’s imagination as it does about Mickey Mouse.

First comes embodiment. Mickey seems to be embodying something for Benjamin. I’m not sure of the exact reference point, it would seem that Benjamin has seen Mickey have an arm removed in one of the cartoons. In these brief notes this image seems to conjure thoughts of ownership and physical limits. Benjamin wonders what this act of arm stealing says about ‘property relations’. It’s a difficult little passage to decipher. It seems that the particular act of theft got him thinking about something to do with possession, even if the point goes unfinished. Perhaps there is something a little like his later project on the Paris arcades happening here, with him gathering short material fragments of an emergent form of modernity. The cartoon is the equivalent of the glass, iron and concrete.

Benjamin switches immediately to what seems like it might be an interest in the cultural diffusion of Mickey Mouse. Rather than being a ‘marathon runner’, he says that the route Mickey takes is ‘more like that of a file in an office’. Perhaps here Benjamin is thinking of how Mickey is discussed by people in passing, how he is a source of conversation and how his notoriety and fame move through networks rather than going directly to the viewer. It’s hard to be sure. The fact that this note starts by indicating that these ideas came after a conversation about Mickey is probably a clue here - Benjamin has encountered Mickey Mouse in this passed-on form.

Following this it is difficult to get much from his observation that ‘in these films, mankind makes preparations to survive civilisation’. Similarly unclear is a point made about how these films show that ‘a creature can still survive even when it has thrown off all resemblance to a human being’. It’s hard to see these cartoons as anything but animals resembling humans, so it is difficult to see how Benjamin reached such a conclusion.

Pointing more towards the storytelling components, Benjamin goes on to make observations on the absence of experience in the cartoons and how the events lack symbolism and atmosphere. These are points that seem to foreshadow some wider ideas he would go on to develop when exploring the impact of media upon ‘aura’. Whereas Benjamin’s observation that ‘all Mickey Mouse films are founded on the motif of leaving home in order to learn what fear is’ relates more closely to his interest in fairy tales. He clearly sees thematic and narrative echoes between those fairy tales and these cartoons. The storyteller takes new form in the cartoon whilst still drawing on the themes of the past.

Finally, Benjamin wonders about the popularity of the Mickey Mouse films. He notes here that it is not just a case of mechanisation drawing people’s attention. It also can’t simply, as he puts it, be put down to ‘misunderstanding’. Rather, and this is where Benjamin hints at the possibility he might have written more and developed his observations further, he thought that aspects of wider social life were somehow encapsulated in relatable ways in the films. As he writes, ‘the public recognizes its own life in them’. Unfortunately we do not hear more on how this works or why this conclusion is reached.

It's a mysterious little fragment. Benjamin’s imagination is clearly fired-up after his viewing and discussion of Mickey Mouse, yet the stretched ideas that appear in his notebook perhaps didn’t give him quite enough of a foundation to write a fuller piece on the cartoons. We should remember that even though it is translated, copy-edited and printed in a nice volume this piece remains just a passing note on something that occurred to the writer. Despite this being just a fragment of thinking, in these lines there are some traces of the interests he was developing concerning broadcast technologies, mediation and mass culture along with a concern for what these mean for experience and cultural reproduction. The little fragment is also suggestive of Benjamin’s ongoing interest in the stories we tell ourselves.